Considering the amount of press coverage the adidas Speedfactory has received, people unfamiliar with footwear manufacturing assume that the use of robotics (or general automation) is new to the footwear industry.

Now read the following the quote and guess when this was said:

“Brightwood, the Florida based manufacturer of athletic shoes, incorporates three Staubli RX90 robots which perform cementing and roughing processes, and is capable of producing 1,800 pairs of lasted shoes in eight hours.

Brightwood owner, Mr. Shaffer says that by using robots in roughing and cementing areas, he can compete with off-shore production where manual labor is doing similar tasks. With two manufacturing operations in China, he, if anyone, is in a good position to testify to that.”

Sounds exactly like the present-day narrative, doesn’t it? Except that this is an excerpt from a 1996 article called ‘Actis and the shoe industry’ written by Anna Kochan. In many ways, the use of robotics is similar to 3D printing in the footwear industry. Both have been around for a long time, but have only recently got their share of publicity.

The earliest use of robotics in the footwear industry can be traced to the 1980’s. Nearly four decades ago, the Scandinavian shoe brand Eccolet SKO (popularly known as Ecco shoes) became the first to integrate robotics into footwear manufacturing.

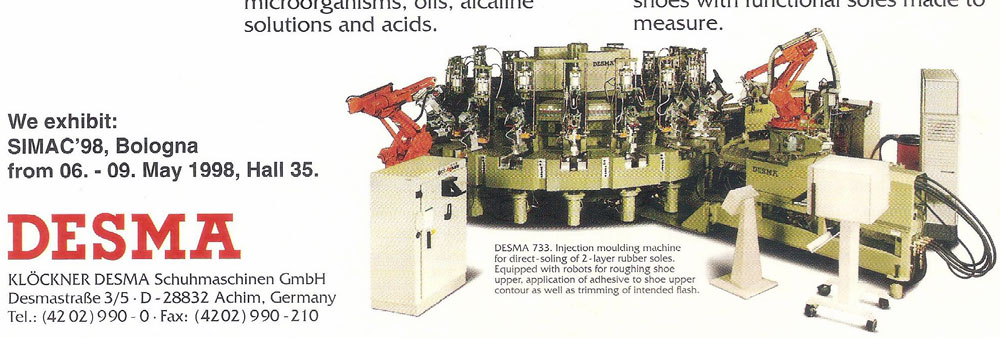

In 1984, Eccolet SKO installed its first robot. By 1996, Ecco had twenty ABB IRB 2000 robots installed across its three of its footwear factories1. And even before the robots arrived, Ecco had partnered with Klockner Desma (a footwear automation company) in 1980 for directly molding soles into its upper.

Throughout the eighties, there were several other examples of footwear companies using robots. Totectors, a safety boot manufacturer from the United Kingdom, first used robots supplied by Unimation2.

By 1996, Totectors expanded its usage of robots to ten, supplied by Staubli Unimation and ABB Flexible automation. These robots worked on the Klockner Desma molding machines where the soles were molded and attached to the upper. The vintage picture (1998) you see above has a similar set-up.

In 1990, Bata collaborated with Ecco (Eccolet SKO) to set up its first robotized production line with three robots which performed functions such as roughing, spraying, and pick-and-place.

And guess what – Ecco wasn’t the first to partner with Desma. In 1977, adidas began using Desma’s automated machine to make its Copa Mundial football boot3. The adidas-Desma collaboration used a round table system for direct soling.

Released two years later in 1979, the adidas Copa Mundial is produced to this day and uses a similar (sole) production method first adopted in 1977.

Watch this video showing the production of the Copa Mundial at adidas’s Scheinfeld factory in Germany. The manufacturing of this shoe involves a far greater degree of automation than what’s seen inside the adidas Speedfactory.

As you can see, the origin story of computerized robotics and automation goes back nearly four decades. But to trace the true historical roots of automation in the shoe industry, we have to time travel back to the 1880’s.

We had previously mentioned Totectors for a reason. Because, more than a century ago, they were one of the first shoemakers to use a Blake Sewer Machine to attach uppers to their soles.

The Blake shoe stitching machine is one of the earliest examples of automation in the footwear industry; this article is a great read if you want to know more. For a comprehensive coverage of footwear manufacturing automation in the 19th century, read this excellent piece from the SaltOfAmerica.

But why does the footwear industry need robotics/automation in the first place?

People who enter a footwear factory for the first time are amazed by how labor intensive shoe-making is. Even after decades of advancements in automation, making a single pair of shoes requires lots of hands.

Like any industrial product, there are four primary reasons for automating footwear production:

1. Speed:

Machines can perform repetitive tasks much faster than a human hand, and often with a fewer number of processes.

2. Consistency or accuracy:

Stitching uppers require a high degree of hand-eye coordination and are prone to errors. While stitching is still mostly manual (human workers operating sewing machines), efforts are being made to introduce automation to the process through innovations such as sew-bots.

Automation has allowed other processes like compound mixing (rubber/foam), component molding, and attaching the sole with the upper to deliver consistent results.

3. Cost savings:

Needless to say, automation has a cost benefit. Increased speed and accuracy allows higher productivity through fewer human operators.

4. Reduction of workplace hazards:

Not only is footwear difficult to produce while maintaining a consistent quality, but it is hazardous as well. For examples, manually cutting upper components requires sharp knives. This dangerous process is now semi-automated through hydraulic cutting presses.

The making of midsoles and outsoles involves the risk of coming in contact with heated materials. Many other processes needed automation – like the ‘roughing’ of uppers using the rotary equivalent of sandpapering, or the trimming of rubber outsoles.

The lasting of shoe uppers was another problem. Running shoes are Strobel lasted, with the edges of the upper stitched to the lasting fabric. But black and brown leather shoes follow a different process. Each shoe is based on a ‘last’ – the foot-shaped mold which gives each upper its unique shape.

In the making of dress and casual shoes, a hard cellulose board is mounted on the last which is then layered with glue. Then the upper edges have to be pulled and stuck on the board before the sole is attached to it. This process is called ‘lasting’ and extremely difficult to be performed manually on an industrial scale.

When lasting a shoe upper manually, one would need a pair of pliers to pull the leather upper over the sides. Remember, you’d need to do this at multiple points over the shoe’s periphery while applying considerable force.

Do this hundred of times a day, and there’s a high risk of repetitive injuries. And needless to say, inconsistencies in quality also becomes inevitable.

So the footwear industry figured out a way to automate the lasting process, using a sophisticated machine which not only pulls the leather over the edges but also glues it over the lasting board.

So introducing automation and robotics in the sole making and lasting process made a lot of sense. Not only did automation make the sole molding safer, but it also increased productivity.

Here are a few videos from Bata Industrials and Desma which show robots engaged in the production of board lasted and direct-soled footwear.

It is obvious the Speedfactory isn’t the first example of automation and robotics in the footwear industry. That being said, there are a couple of new processes seen in the Speedfactory video. So at best, it is an incremental evolution over what the industry has achieved so far.

It is also evident that even adidas has been using robotics in footwear manufacturing for a very long time. Here’s an old video from adidas’s Sheinfeld factory in Germany. This factory makes the Copa Mundial football and smaller batches of other custom products.5

As you can see, adidas’s own ‘Made in Germany’ factory predates the Speedfactory by over a decade. There’s a healthy amount of automation involved in the making of the Copa Mundial football boot.

Here’s an interesting observation. Europe has led most of the advancements in footwear manufacturing. But coming to think of it, this doesn’t come as a surprise.

Europe has centuries of experience in shoe making, so it was natural that the handcrafted art gradually adapted itself to the industrial age. It also helped that countries like Germany have traditionally excelled in engineering, so it was a happy marriage of shoemaking and the former.

Need proof? Kuka, the popular robotics company is German and so is Desma – a company focused exclusively on footwear manufacturing automation. Staubli robotics is Swiss. ABB is German, and so is Kurtz Ersa, the company which makes machines producing the Boost midsole.

By the way, Asian manufacturing also isn’t going away. China is also quickly adopting robotics, so automation isn’t territory exclusive. If anything, the combination of robotics and cheaper human operators will make the Asian source-base even more lucrative. But what of the production lead-times?

A misleading narrative is that athletic shoes take 18 months to produce, and something like the adidas Speedfactory will reduce that to weeks, days, or even hours. That is utter nonsense.

The oft-mentioned 18 month lead-time isn’t the time taken to produce a pair of shoes. Rather, it represents the entire go-to-market (GTM) process for a particular shoe model.

The GTM calendar is a different beast altogether. It is constituted of other processes like multiple design iterations, collecting orders from retailers, demand forecasting, production planning, commercialization trials, and then shipping to retail. The actual production time only forms a small part of this calendar.

And what of all the fear-mongering about the robots taking over jobs? Regardless of the level of automation, there will always be jobs for human operators. It is just that skills which are in use today might not necessarily be useful for the jobs of tomorrow.

Read the following excerpt from an article which is about the invention of the Blake Sewer in 1885. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

“ …the function of the Blake Sewer was to quickly and efficiently attach the soles to the uppers. The machine was a sensation. For the first few days of its use the machine and its operator had to be locked up to ensure their safety, such was the alarm amongst the Denton workforce. All fears of violence, however soon subsided when it was explained the Blake Sewer would greatly increase output and provide more work for everybody.”4

(Related: What’s inside the adidas Speedfactory?)

Reference/sources:

1.http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/01445159610126393

2, 4.http://www.rushdenheritage.co.uk/shoetrade/totectors100yrs.html

https://issuu.com/symphonypublishing/docs/footwearplus_ecco (page 2, 1980 Desma)

3http://www.desma.biz/fileadmin/desma/enews/August_September_2015/DESMA_CHONICLE_1965-2015_EN.pdf

https://www.thoughtco.com/textile-revolution-1991934

world.bata.com/news/2013/netherlands-leads-way-bata-industrials-efficiency-and-accreditation/

“Robots bring automation to shoe production” Brian W Rooks, Sep 1st 1996

“Factory floor robot programming” by Luhr, Budenbender and Brube. Shoes and more, volume 3, number 2 Huthig publishing. February 1998

http://saltofamerica.com/contents/displayArticle.aspx?19_346

http://news.adidas.com/US/images-and-videos/ALL/adidas-production-in-scheinfeld-germany/a/b709e6da-bcbf-42aa-aa0e-5e73852863a7

http://blog.adidas-group.com/2012/10/on-the-path-that-adi-dassler-set-%E2%80%93-shoes-made-in-germany/

5www.tactics.com/info/adidas-skateboarding-busenitz-scheinfeld