This is how the Nike Zoom Structure’s of old used to look like. Full length EVA midsole, with a medial post of harder density. The image shown is that of Zoom Structure 14.

Till three years ago, the Nike Zoom Structure used to be a simple affair, like it had been for many years before. A full length foam midsole, with a harder density foam wedge on the inside of shoe. The Nike Zoom Structure was classified as a stability shoe, which worked on the following premise: a runner who had a low arch or flat feet was more likely to excessively roll his or her foot inwards while landing, and this kind of motion was supposedly, and potentially harmful.

The theory also assumed that most runners would land on their heel or rear foot, so the gait cycle would start in the rear and work its way forward. The harder foam wedge would help arrest that excessive inward foot roll, protecting the runner from the potentially damaging effects of excessive pronation. This concept spawned an army of stability shoes across multiple brands, each with their own variation of pronation control mechanism. Today, this theory might seem like a generalization and oversimplification of how the foot works, and running footwear in general is a subject of much debate. But since no two runners are born alike, stability shoes worked with different degrees of success across the community.

Much water has flown under the bridge since the Nike Zoom Structure 14, and the Zoom Structure 17 has little in common with what it once used to be. From the conventional looking Zoom Structure 15, the sole design took a quantum evolutionary leap in the 2012 Structure 16, and the same design carries forward to Zoom Structure 17. Bottom of the shoe is where big shifts happen, which in much part is buoyed by triumphant success of models like the Nike Lunarglide.

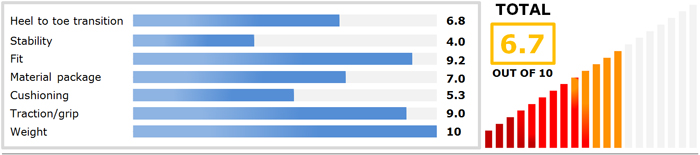

The new Zoom Structure 17 sheds the traditional high density foam piece and transitions to a midsole construction which uses two densities of foam fused diagonally together. This is a now familiar sight in Nike models like the Lunareclipse 4 and the Lunarglide 5. The idea is that placing angled sections of dual density foam together results in a much smoother movement, and controls pronation gradually. The online Nike store describes the Zoom Structure 17 as ‘Ultimate stability in a responsive ride’.

What if we told you that the last sentence above is far from an accurate description of what the Zoom Structure 17 actually is? For there is nothing stable about the Zoom Structure 17. The way we look at it, the shoe is more motion control and less stability, and the two aren’t synonyms in this case.

With the soft Cushlon foam wedge on the outer side and the firmer foam casing on the inside, the Structure 17 tries to slow down pronation by keeping all the weight on the softer side. As a consequence, each stride feels like the foot is permanently leaning on outer side of the shoe. In essence, the Zoom Structure 17 tries to control pronation by inducing massive instability. A true paradox if ever there was one.

Speaking of Nike’s official description of the Zoom Structure 17, its ‘Featured technology’ section also mentions use of Flywire. There isn’t a yarn of Flywire in the Zoom Structure 17, so the blunder is probably a cause of cut and paste getting the better of a tired content writer. What’s surprising though, is that no one seems to have noticed it so far.

We said good things about the Lunarglide 4 and Lunareclipse 4, so why the ire on the Zoom Structure 17? Aren’t these shoes similar? No, because the Structure is not built the same way as the aforementioned models, and therein lies the reason behind difference in our opinion. The Glide and Eclipse differs from the Structure 17 in one big way. The angle at which the different densities of foam stack together is very gradual, and both layers completely overlap each when viewed side to side.

The outcome of which is that both Lunarglide and Lunareclipse work as promised, gradually slowing down the rate of inward foot roll (pronation) during the gait cycle. The Zoom Structure 17, in contrast has two densities of foam stacked together at an extremely sharp angle, and there is no overlap once the wedges meet each other. With that set-up, every impact results in the foot leaning excessively towards the softer side. The ride experience is anything but gradual, and feels very unnatural. If Nike chose to emulate the Glide and Eclipse, the Zoom Structure fails in its objective.

We suspect that the choice of manufacturing process has led to this happening. The Lunarglide and Lunareclipse have two separate components of foam stacked atop each other, and this allows much greater freedom in how the foam pieces are shaped. The Zoom Structure 17 uses a rather unperfected technique – that of fusing together two densities of foam in an injection molding process. This limits the angle at which two foam densities can be beveled, and material bleeding over each other is all so evident when you look at the undersole (see picture and notation above).

The white area is soft Cushlon foam. The black foam is higher density. Naturally, all the cushioning is only on one side of the shoe.

Is there cushioning? There’s plenty of it, but all only on one side of the shoe. The white Cushlon foam extends from the heel to the forefoot, so most of the compression is delivered in a manner best described as lopsided. The foam is responsive, but the overall feeling of cushioning inconsistency cannot be shrugged off. The Nike Zoom Structure 17 is a great example of fixing something which was unbroken in the first place. We do hope the new Zoom Structure 18 in August 2014 features improvements which makes it equal to the task.

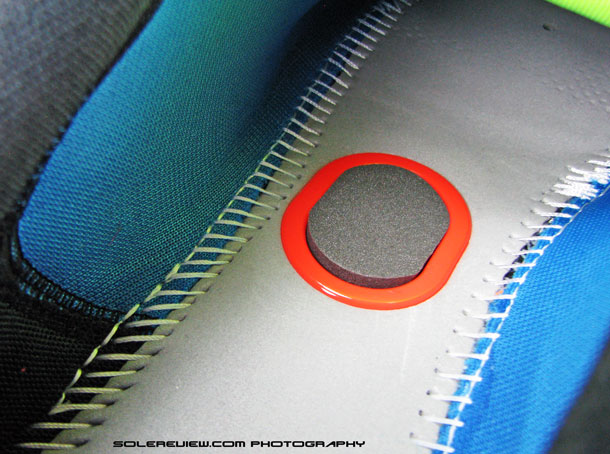

The shoe uses Zoom Air bags in the forefoot, and what it does is make the forefoot area very stiff, despite very prominent flex grooves. The sockliner also adds to the rigidity too; the top layer is a soft foam but is cupped all around (except the arch area) by a stiff foam, with reinforced areas under the forefoot and heel. The name ‘Fitsole 2’ is very confusing; the Nike Air Pegasus 30 also featured a Fitsole 2, but that is made of a completely different material.

This might mislead runners who liked the memory foam like give of the Pegasus Fitsole 2 sockliner, and assume that Zoom Structure 17 has the same insole. Both are very different components with the same name, and we’re glad Nike is changing names on running sockliners starting this Fall. The Air Pegasus 31 is the first to feature that change.

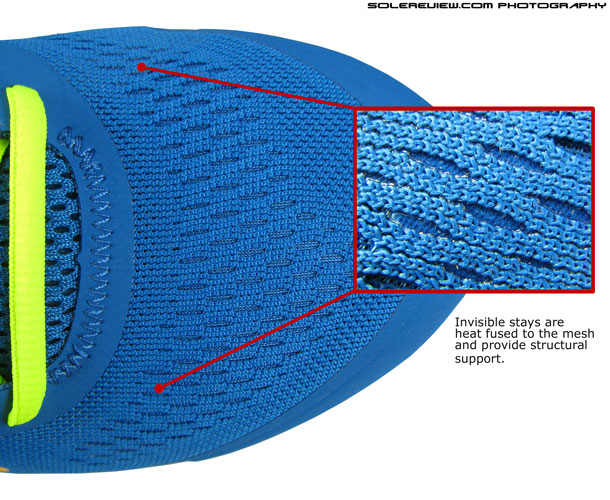

For fortunate souls who found the Zoom Structure 16 suitable for their running needs and want to know about upper changes on the Structure 17, there’s plenty to cheer about. There’s a mile long list of new updates to the upper design. In a way, it is a Pegasus 29 vs. 30 deja vu all over. The stitched-on synthetic leather panels of the Zoom Structure 16 have been replaced with thin layers of fused overlays which show bulky aesthetics the door. The fused panels are used sparingly, with areas like the toe bumper and eye stay getting most of the treatment. There are no overlays running across the top of the toe-box; instead, invisible support stays are heat fused to the upper from beneath to add structural strength. (see image above).

The conventional spacer mesh is replaced by a Lunarglide-ish engineered mesh which features vents or close knit areas, depending on which area of shoe it covers. The mid foot and heel area is completely cleaned up, with overlays being minimized and replaced with mesh. In rear-foot, a see-thru mesh is fused over the heel, partially exposing slit underlays. Night time visibility is a big minus, with no shiny elements on the shoe at all. There used to be small reflective strip in the Structure 16 forefoot, but that is gone in the current version. If you need reflectivity on the Structure 17, customizing your shoes on Nike ID is the only way out – at a premium, of course.

Sweeping changes happen in the mid foot area, where the construction upgrades itself to an internal sleeve. The tongue is now stitched to its sides, getting rid of the ungainly tongue slide of the Structure 16. Inside the upper, there’s hardly any seam, except for the tongue gusset and collar attachment, so the fit is superb. The entire lining forward of the rear foot seam is a foam padded mesh, so there’s a confidence inspiring sensation of wrap around the foot. The elevated sense of fit is further heightened by the use of dynamic support straps on the inner side, giving the arch a nice wrap from base of the upper to the laces. Overall, the fit is a vast improvement over the 2012 Nike Zoom Structure 16.

If the Zoom Structure 16 worked for you, the 17th version is greatly improved and will make you happier than the 2012 version. The upper is completely new, the shoe is lightweight, and the updates addresses many areas where the Structure 16 was found wanting. But in our viewpoint, the Zoom Structure 17 is a not a shoe we would prefer to run in. The way the shoe manages pronation does not inspire us, and it over-corrects footstrike – which we don’t see as healthy. The shoe might have good intentions – that to correct excessive pronation, but like they say, you can’t have too much of a good thing.

Don’t get us wrong. We admire Nike for constantly pushing the envelope, but the Zoom Structure 17 seems to be a case of overzealous experiment. If you’re out on the streets looking for a stability shoe which also offers ample cushioning, we recommend that you either buy the Lunareclipse 4, Asics Kayano 20, or wait for the new Zoom Structure 18 in October. Unless you were treated well by the Zoom Structure 16 – in that scenario, there’s no cause for alarm.

(Disclaimer: Solereview paid full US retail price for the shoe reviewed)

Update, November 4th, 2014: Here’s the review of Zoom Structure 18

1 comment

Visitor Rating: 5 Stars

I have had Structure 16’s these were ok on my gait test but not great… Structure 17 performed badly on gait. I overpronate as I land and to combat this I am advised New Balance 860v5. Do you think this is a good idea? I am a 10 in the Nikes and was going to choose 10 in new balance also but maybe 2e width. Thoughts greatly appreciated.

Comments are closed.